Welfare label ensures a premium for meat and eggs

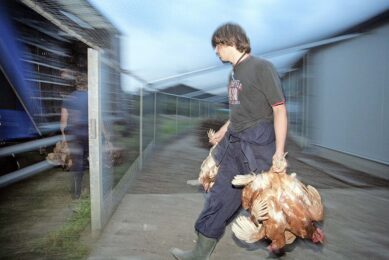

A group of poultry farmers in the French department of Sarthe focuses on animal welfare. The word ‘Liberté’ (liberty) is proudly printed on egg cartons and poultrymeat packaging. Several quality labels are designed to persuade consumers to spend more money on animal-friendly eggs and meat.

Working together

Dutch company Moba installed brand new robots at its egg packing station L’Oeuf in the village of La Bazoge. The robots are capable of doubling capacity. That may not seem much but instead of just one farm’s eggs, the eggs of more than one farm can now be packed in an egg carton, each one with a stamp on it that shows the origin per farm, ensuring egg traceability. It means that the transporters used to sort boxes with the packed eggs can be used far more intensively. “Instead of 40,000 eggs per hour, we can now manage 80,000,” explains proud owner Christophe Bériard. He has welcomed many visitors from abroad who wanted to catch a glimpse of the new robots. He prefers not to say how much they cost.

The village of Loué, near Le Mans, looks like a typical French village: small, peaceful and quiet. A statue of a large chicken at the entrance to the village immediately catches your attention. This is what the northwestern region is all about. There are 1,200 poultry farmers (200 with laying hens, 1,000 with broilers) in a 25 kilometre radius around Loué. The village’s name even made it into a brand that is sold in supermarkets around the country. Poultry farmer Didier who, incidentally, bears a surprising likeness to soccer legend Didier Deschamps, advertises the brand on large posters with a nod to the French soccer coach.

Instead of 40,000 eggs per hour, we can now manage 80,000.”

Originally, Loué had a large poultry market that turned into a strong poultry sector. For many farms it was lucrative to keep poultry in addition to beef cattle and arable farming. One or two have specialised. It is the birthplace of the LDC Groupe. With 16,000 employees in France, 6,000 abroad and a turnover of € 4.1 billion, it is by far the largest company in the French poultry chain. Founded in 1968, the family company has multiple poultry slaughterhouses, feed companies, egg packing stations, breeding farms and egg and meat processing facilities.

Cavol, a modern company and part of the LDC Groupe, slaughters and processes half a million UBA chickens a week in Loué. Every week, some 3-4,000 kilograms of the meat finds its way to Dutch supermarket chain Albert Heijn to be sold as 2-star meat. Other buyers include McDonalds, Kentucky Fried Chicken and Marie, a popular brand in France.

Poultry welfare labels

The company is completely focused on producing poultry with 3 different welfare labels: organic, free range and the French Label Rouge. This label is issued by the French government and places high demands on animal welfare to obtain its 3 stars. The broilers are a slower growing breed and live much longer than regular broilers: 81 days. They also have more space: 4.3 chicks per square metre, including outside free-range. 400,000 broilers leave the slaughterhouse under the Label Rouge.

Country reports:

Takes a look at the poultry industry in countries around the world.

Above and beyond on poultry welfare measures

The Loué brand goes even further with a bird age of 84 days, 4 m2 instead of 2 m2 per chicken outside and several other requirements, such as antibiotic reduction and contributing to greening the landscape. The poultry farmers have planted a million trees over the years, as well as 1,800 kilometres of hedges.

The grain for their feed is 80% local (27,000 hectares). Poultry vet Martine Cottin, employed by the slaughterhouse, advises poultry farmers on reducing antibiotics, for example, by using homeopathy and phytotherapy. Even the slaughter of the birds complies with welfare measures: stunning with CO2 and keeping the poultry in a dark room prior to slaughter. Cavol slaughters 400,000 Label Rouge broilers and 40,000 Loué chickens, in addition to the 60,000 organic chickens reared under the Nature and Respect label.

Impact of Covid pandemic

Marketing director David Le Manour has seen increased sales of the 3 labels: 10% in 2019. The € 35 million invested in expansion and modernisation over the last few years is therefore not surprising. He had been expecting stable growth before the coronavirus pandemic. However, this is uncertain now. The question is whether consumers will keep buying given the considerable price difference. Where a standard supermarket fillet costs € 7-9 per kg, a Label Rouge fillet may be € 20-22, with Loué at € 28 and organic even as much as € 30. Le Manour does not mention how much poultry farmers receive. He does say that they agreed upon fixed prices beforehand, in consultation with the poultry farmers cooperative Cafel. The price changes every 3 months depending on the grain price.

One poultry farmer’s story

“I do not want my birds to be too big.”

Poultry and arable farmer Olivier Complain (53) has 4 poultry houses each with 4,000 broilers, chickens and cockerels. They will go to the slaughterhouse in 10 days. The current price is € 2.17 per kg and his birds weigh 1.515 kgs on average when he delivers them. This has not increased by even 10 grams over the years. “I do not want my birds to be too big,” he says. “Call me old-fashioned, but they perform well and taste accordingly.”

Summer is the biggest challenge

Their health and growth are not his biggest problems because these aspects are all fine. He hardly uses antibiotics and he cannot remember the last time he used anti-coccidiostats. No, his biggest problem is to get his birds inside in summer.

If he does not get them inside, they may fall prey to foxes, hedgehogs – who like the young chicks – or even villagers who sometimes just steal a chicken. “The police do nothing,” he complains. Altogther, the 1,100 broiler farmers in the region lose about 140,000 birds a year. It’s the price they pay for free-range. But Complain has another problem: the paper tiger. “Oh well, that’s no different anywhere else in the world,” he adds with a smile.

Webinars

Poultry World presents webinars on various topics within the poultry production sector – if you missed them they are now available to view!

3 factors that determine the future of poultry welfare

Animal welfare may well be a focal point, but LDC Groupe CEO Gilles Huttepainde cannot predict what the future will bring for poultry welfare. “It is very uncertain.” He draws a triangle to illustrate the factors on which development depends: a good price, society’s willingness to pay extra and welfare demands. Ideally, these 3 factors will overlap in the middle of the triangle. “However, no one knows whether that will actually happen.” LDC Groupe nevertheless fully embraces welfare. Now, about 25% of its poultry farmer members operate under the ‘welfare’ label. The company wants all its members to comply with the strict demands of Nature d’Eleveur by 2050 (see box).

Constantly looking for innovations

Poultry farmer Julien Leballeur (32) switched to a new way of populating his welfare poultry house with broilers. Not with chicks, but with breeding eggs instead. It’s a remarkable sight: the floor scattered with broken eggshells and chicks scratching around happily in the warm poultry house. They hatched only a few hours ago and can already manage to find their way to the feeders. A scientific institute in Tours conducted tests with hatched eggs. The researchers showed that is better for the chicks’ welfare to hatch inside the poultry house. It causes less stress and, supposedly, less mortality. The poultry farmer recalls that he had 1% mortality due to eggs that did not hatch and chicks that were not viable.

It is not the first time that Leballeur has done pioneering work.

- His 2010 poultry house was the first to have large windows, perches and more space for the chickens than needed. Soon, he will go from 19 to 15 chicks per m2.

- There are demands to save the environment as well, to integrate the farms into the landscape, to use French feed and French birds and to have a 10 cm thick layer of straw on the floor as litter. There are also measures to prevent disease as much as possible without the use of antibiotics and anti-coccidiosis.

- Music in the poultry house is new, as well as pecking stones with added vitamins and toys for the birds.

- The supply of eggs, already sexed in ovo, is another recent development.

Leballeur operates under the Nature d’Eleveurs (Nature poultry farmers) welfare label founded by the LDC Groupe. He does good business. “In addition to poultry, I also have beef cattle, finishers and arable farming. Thanks to the fixed price agreements with the slaughterhouse and feed company, I get the best financial results from my poultry.”

Author:

Hans Siemes, freelance correspondent

Join 31,000+ subscribers

Subscribe to our newsletter to stay updated about all the need-to-know content in the poultry sector, three times a week. Beheer

Beheer

WP Admin

WP Admin  Bewerk bericht

Bewerk bericht