New Campylobacter vaccine for poultry

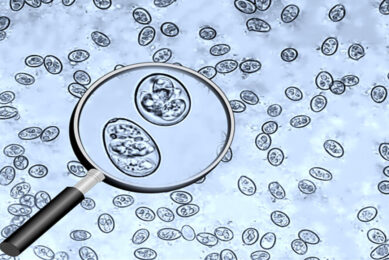

A new poultry vaccine in development at the University of Arizona offers a unique approach in controlling Campylobacter jejuni infection in chickens.

Trials have shown that the vaccine significantly reduced the pathogen’s ability to colonise young chickens’ intestines, where the infection begins. The goal is to halt the contamination before it spreads and survives on raw chicken sold in stores.

“Chickens don’t actually cause the disease, nor does it make them ill. It’s the organism they carry that makes people sick,” said Lynn Joens, a professor in The University of Arizona Dept of Veterinary Science and Microbiology.

Funded by the USDA, Joens and UA graduate students started analysing Campylobacter’s infection process about 4 years ago, looking for a way to interrupt it. The laboratory team discovered that the pathogen first attached itself to the surface of the chick’s intestines and then began to multiply. Attacking the “sticking” mechanism seemed to be the key.

When the UA researchers sequenced the intestinal surface protein they identified the gene responsible for producing Campylobacter’s adherence protein. Then they built a trial vaccine around it using Salmonella bacteria as a vector. The adherence gene was inserted into Salmonella bacteria, which is nonpathogenic for poultry. The resulting live vaccine – containing Salmonella programmed to make the Campylobacter adhering protein – was fed to young chickens to protect them.

“Once the Salmonella in the vaccine produced the Campylobacter protein, the chicks made antibodies against it in their intestines,†Joens says. “In our first study of 15 birds we got a very significant reduction – 98% – in Campylobacter infection, compared with a control group. We’re now repeating the trial on a larger scale.”

Joens’ preliminary figures show that 270 million Campylobacter organisms were present in non-vaccinated birds, compared with 67,000 organisms in the vaccinated birds.

“You need at least 500 organisms to produce disease in humans,” he explained. “The chlorine in the packinghouse chillers usually reduces numbers of bacteria by 1,000 to 100,000 organisms, so the chickens should be free of Campylobacter after processing.”

The UA group was the first to discover the adherence protein, which is only produced when Campylobacter jejuni colonizes certain surfaces, like chicken intestine and skin. They have a patent pending in both the US and the EU for the gene that produces it.

“If everything goes right we could have a commercial vaccine in 3-5 years,” Joens said.

Source: University of Arizona

Join 31,000+ subscribers

Subscribe to our newsletter to stay updated about all the need-to-know content in the poultry sector, three times a week. Beheer

Beheer

WP Admin

WP Admin  Bewerk bericht

Bewerk bericht